Software Engineering Series - Article 3

Significance, Purpose, and Principles of System Testing

System testing is the process of executing a program with the intent of finding errors. A successful test is one that uncovers a previously undiscovered error.

The goal is to find potential bugs and defects using minimum manpower and time. Users should design test cases based on requirements, design documents, or the internal structure of the program, and use these cases to run the program to find errors.

Information system testing includes software testing, hardware testing, and network testing. Hardware and network testing can be conducted based on specific performance indicators. Here, we focus primarily on software testing.

System testing is critical for ensuring quality and reliability. It serves as the final review of system analysis, design, and implementation. Follow these basic principles:

- Test early and often. Testing shouldn’t wait until development is finished. Errors can creep in at any stage due to complexity or communication issues. Testing should be integrated throughout the lifecycle to catch and fix errors early.

- Avoid testing your own code. Developers often have a blind spot for their own work or subconsciously follow the same logic used during coding. Testing should be handled by an independent team for objectivity and effectiveness.

- Define expected outputs. When designing test scenarios, determine both the input data and the expected result. Comparing the actual output with the expected result is how you identify defects.

- Include invalid and unexpected inputs. Don’t just test “happy paths.” People tend to test correct scenarios and ignore abnormal or illogical inputs, which is often where hidden bugs reside.

- Check for unintended side effects. Test not only if the program does what it should do, but also ensure it doesn’t do what it shouldn’t. Extra, unintended functions can impact efficiency or cause potential harm.

- Stick to the plan. Avoid random testing. A test plan should include content, schedule, personnel, environment, tools, and data. This ensures the project stays on track and everything is coordinated.

- Save test documents. Keep test plans and test cases as part of the software documentation for easier maintenance.

- Design for re-use. Well-designed test cases make re-testing or incremental testing easier. When fixing bugs or adding features, you’ll need to re-run tests. Reusing or modifying existing cases is much more efficient.

Testing objectives for the system testing phase are derived from the requirements analysis phase.

Traditional Software Testing Strategies

Effective software testing typically follows four steps: Unit Testing, Integration Testing, Validation (Confirmation) Testing, and System Testing.

(1) Unit Testing

Also known as module testing. It occurs after a module is written and compiles without errors. It focuses on internal logic and data structures. Usually performed using white-box testing. Multiple modules can be tested simultaneously.

1. Content of Unit Testing

Unit testing checks five main characteristics:

- Module Interface: Ensures data flows correctly in and out.

- Do input parameters and formal parameters match in count, type, and units?

- Do actual parameters match the formal parameters of called modules?

- Are standard function parameters correct?

- Are global variables consistent across modules?

- Does the input only change formal parameters?

- Are I/O formats consistent?

- Are files opened before use and closed after?

- Local Data Structures: Common source of errors.

- Are variable declarations appropriate?

- Are uninitialized variables used?

- Are default/initial values correct?

- Are there typos in variable names?

- Critical Execution Paths: Testing paths is fundamental. Since exhaustive testing is impossible, design cases to find math, comparison, or control flow errors.

- Math errors: Operator precedence, precision issues, incompatible types, algorithm flaws.

- Comparison/Control flow: Precision causing “equal” values to differ, comparing different types, incorrect logic operators, off-by-one errors in loops, infinite loops, or incorrect exit points.

- Error Handling: A good design predicts error conditions and has a path to handle them. Logic must be correct to allow for user maintenance.

- Boundary Conditions: Testing the edges of the software’s capabilities. Errors frequently occur at boundaries.

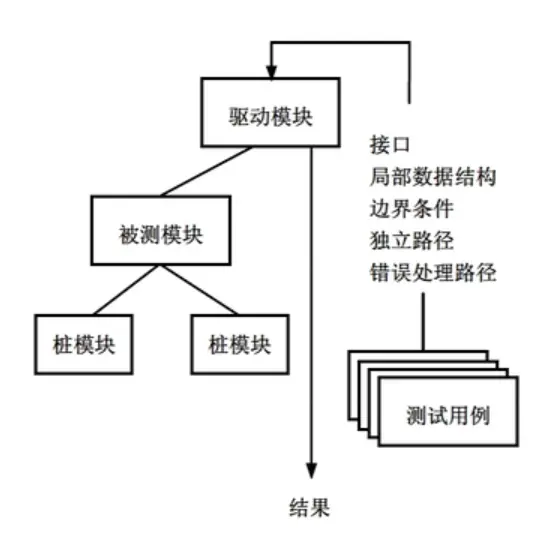

2. Unit Testing Process

Since modules don’t run in isolation, you need two types of helper modules:

- Driver: Acts as a “main” program. It accepts test case data, passes it to the module under test, and prints results.

- Stub: Replaces sub-modules called by the module under test. It performs minimal data processing to verify the interface and return information.

High module cohesion simplifies unit testing. If a module performs only one function, it requires fewer test cases and errors are easier to predict.

(2) Integration Testing

Integration testing combines modules according to the system design. Even if modules work individually, problems can arise when they interact.

Two main approaches: Non-incremental integration (Big Bang - test all at once) and Incremental integration (building and testing in small steps).

Common incremental strategies:

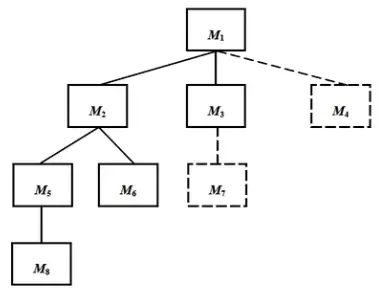

1. Top-Down Integration

Constructs the architecture starting from the main control module (main program) and moving down the hierarchy using depth-first or breadth-first search.

- The main control module is the driver; stubs replace its subordinates.

- Replace stubs one by one with actual modules based on the chosen search method.

- Test after each integration.

- Perform regression testing to ensure no new bugs were introduced.

- Repeat until the structure is complete.

Pros: No drivers needed. Cons: Requires writing stubs.

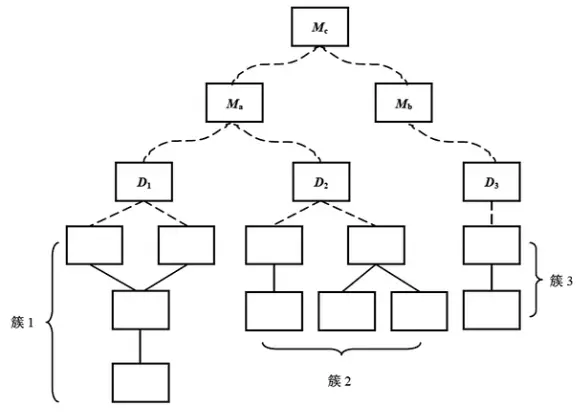

2. Bottom-Up Integration

Starts construction and testing with atomic modules (lowest level). Since subordinates are always available, stubs aren’t needed.

- Combine low-level modules into clusters that perform sub-functions.

- Write a driver to coordinate test inputs and outputs.

- Test the cluster.

- Remove the driver and move up the hierarchy.

Pros: No stubs needed. Cons: Requires writing drivers.

3. Regression Testing

Every time a new module is added, the software changes. New data paths or control logic might break existing functionality. Regression testing re-executes a subset of previous tests to ensure changes haven’t introduced side effects.

Tests should include:

- Representative samples of all functions.

- Tests focused on components likely affected by the change.

- Tests focused on the changed components themselves.

4. Smoke Testing

A frequent integration testing method for time-critical projects. It allows the team to assess the project status daily.

Testing Methods

Software testing involves specific methods and case designs within a sequence of steps. Methods are divided into static and dynamic testing.

- Static Testing: Does not run the code. Uses manual inspection or computer-aided tools.

- Manual: Code reviews, static structure analysis, code quality metrics.

- Computer-Aided: Tools extract info to check for logic defects or suspicious constructs.

- Dynamic Testing: Running the program to find errors. Includes black-box and white-box testing.

Test cases consist of input data and expected results. They must include both valid and invalid input conditions.

(1) Black-Box Testing

Also called functional testing. It treats the software as a “black box,” testing external behavior without looking at internal code or structure.

Techniques include:

- Equivalence Partitioning: Divide input data into classes; test one representative from each class.

- Boundary Value Analysis: Focuses on the edges of input/output ranges, as errors often cluster there.

- Error Guessing: Based on experience and intuition about where bugs typically hide.

- Cause-Effect Graphing: Using logic diagrams to map inputs (causes) to outputs (effects) to create a decision table.

(2) White-Box Testing

Also called structural testing. It designs cases based on internal logic and structure to verify paths and design requirements.

Principles:

- Every independent path is executed at least once.

- Every logical decision is tested for both True and False outcomes.

- Loops are tested at boundaries and typical values.

- Internal data structure validity is verified.

1. Logic Coverage

Measures how thoroughly the code logic is exercised:

- Statement Coverage: Every statement runs at least once (the weakest criteria).

- Decision (Branch) Coverage: Every decision evaluates to both True and False.

- Condition Coverage: Every logical condition in a decision takes on all possible values.

- Decision/Condition Coverage: Satisfies both Decision and Condition coverage.

- Condition Combination Coverage: Every possible combination of condition outcomes in a decision is tested.

- Path Coverage: Every possible execution path in the program is tested.

2. Loop Coverage

Ensures every condition within a loop is verified.

3. Basis Path Testing

Derived from control flow graphs. It analyzes cyclomatic complexity to define a set of basic execution paths for test design.

Debugging

Debugging happens after testing. Its job is to find the cause and location of a bug and fix it.

Common methods:

(1) Trial and Error (Brute Force)

The developer guesses the problem location, inserts print statements, or checks memory/registers to find clues.

(2) Backtracking

Start from where the error was detected and trace the code backward through the control flow to find the root cause.

(3) Binary Search (Partitioning)

Isolate the error by checking variables at specific points. If a variable is correct at point A but wrong at point B, the error is between those points. Repeat to narrow the scope.

(4) Induction

Start with specific clues from the failed test, collect data, look for patterns, form a hypothesis, and prove or disprove it.

(5) Deduction

List all possible causes, use data to eliminate impossible or contradictory ones, pick the most likely cause, refine the hypothesis, and see if it explains all test results.