Software Engineering Series Article One

Software Process

The roadmap followed during software development is called a “software process.”

Capability Maturity Model (CMM)

CMM divides software process improvement into the following 5 maturity levels:

Initial

Software is characterized by disorganization, sometimes even chaos. There are almost no clearly defined steps, and project completion relies entirely on individual efforts and the actions of heroic key figures.

Repeatable

Basic project management processes and practices are established to track project costs, schedules, and functional characteristics. Necessary process guidelines are in place to repeat previous successes on similar projects.

Defined

Both management and engineering software processes are documented, standardized, and integrated into the organization’s standard software process. All projects use this standard software process, modified as needed, to develop and maintain software.

Managed

Detailed metrics for software process and product quality are defined. Both the software process and product quality are understood and controlled by members of the development organization.

Optimized

Quantitative analysis is enhanced. Feedback from process quality and new ideas/technologies allows for continuous process improvement.

The CMM model provides a framework that organizes the evolutionary steps of software process improvement into 5 maturity levels, laying a progressive foundation for continuous process improvement. These 5 maturity levels define an ordered scale to measure an organization’s software process maturity and evaluate its software process capability.

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI)

CMM’s success led to the derivation of models applicable to different disciplines. However, engineering often involves multiple cross-disciplines, making it necessary to integrate various process improvement efforts. CMMI is a synthesis and improvement of several process models.

CMMI offers two representations: staged and continuous models.

1. Staged Model

The staged model’s structure is similar to CMM, focusing on organizational maturity. CMMI-SE/SW/IPPD version 1.1 has 5 maturity levels:

- Initial: Processes are unpredictable and lack control.

- Managed: Processes serve the project.

- Defined: Processes serve the organization.

- Quantitatively Managed: Processes are measured and controlled.

- Optimized: Focuses on process improvement.

2. Continuous Model

The continuous model focuses on the capability of each process area. An organization can achieve different Process Area Capability Levels (CL) for different processes. CMMI includes 6 process area capability levels, numbered 0-5. Capability levels include common goals and related common practices, which are added to specific goals and practices within the process area. When an organization satisfies the specific and common goals of a process area, it is said to have achieved that process area’s capability level.

- CL0 (Incomplete): The process area is not performed or does not achieve all goals defined for CL1.

- CL1 (Performed): Its common goal is that the process transforms identifiable input work products into identifiable output work products to achieve the specific goals supporting the process area.

- CL2 (Managed): Its common goal focuses on institutionalizing managed processes. Based on organizational policies, it specifies which process operation will be used. Projects follow documented plans and process descriptions, all working personnel have access to sufficient resources, and all work tasks and products are monitored, controlled, and reviewed.

- CL3 (Defined): Its common goal focuses on institutionalizing defined processes. Processes are tailored from the organization’s standard process set according to organizational tailoring guidelines. Process assets and process measurements must also be collected and used for future process improvement.

- CL4 (Quantitatively Managed): Its common goal focuses on institutionalizing quantitatively managed processes. Measurements and quality assurance are used to control and improve process areas, and quantitative objectives for quality and process performance are established and used as management criteria.

- CL5 (Optimized): Quantitative (statistical) means are used to change and optimize process areas to meet evolving customer requirements and improve the effectiveness of process areas in continuous improvement plans.

Software Process Models

Software process models are also commonly known as software development models. They provide a structural framework for all processes, activities, and tasks in software development. Typical software process models include the Waterfall model, Incremental model, Evolutionary models (Prototype model, Spiral model), Fountain model, Component-Based Development model, and Formal Methods model.

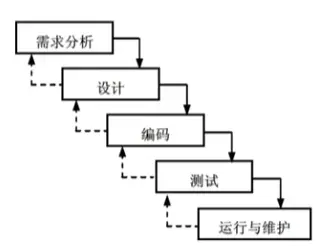

Waterfall Model

The Waterfall model defines software lifecycle activities as several linearly connected stages, including requirements analysis, design, coding, testing, operation, and maintenance. It mandates a fixed, sequential order, flowing step-by-step like a waterfall.

The Waterfall model offers an effective management paradigm for software development and maintenance. Based on this model, development plans are made, cost budgets are set, development teams are organized, and the entire development process is guided effectively through phase reviews and document control. Therefore, it’s a document-driven model, suitable for software projects with very clear requirements.

The Waterfall model assumes that the requirements for a system under development are complete, concise, consistent, and can be fully defined before design and implementation begin.

Advantages of the Waterfall model include ease of understanding and low management costs. It emphasizes phased early planning, requirements gathering, and product testing. Disadvantages include: customers must be able to express their needs completely, correctly, and clearly; it’s difficult to assess the true progress status in the initial two or three phases; a large amount of integration and testing work emerges as the project nears completion; and the system’s capabilities cannot be demonstrated until the project’s end. In the Waterfall model, errors in requirements or design are often only discovered late in the project, leading to weaker project risk control. This often results in project delays and budget overruns.

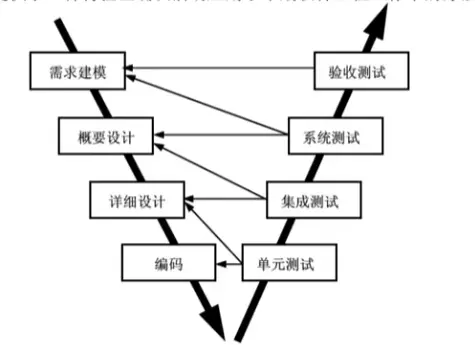

V-Model

A variant of the Waterfall model is the V-Model.

The V-Model describes the relationship between quality assurance activities and communication, modeling-related activities, and early construction-related activities. As the software team progresses down the left side of the V-Model, fundamental problem requirements are progressively refined, forming technical descriptions of problems and solutions. Once coding is complete, the team moves up the right side of the V-Model, essentially performing a series of tests (quality assurance activities). These tests verify each model generated as the team moved down the left side of the V-Model. The V-Model provides a way to apply verification and validation activities early in software engineering.

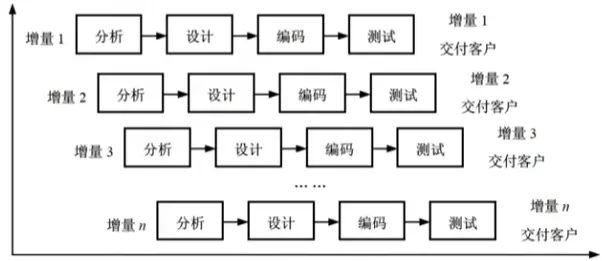

Incremental Model

The Incremental model combines basic elements of the Waterfall model with the iterative features of prototyping. It assumes that requirements can be segmented into a series of incremental products, each of which can be developed separately. This model uses interleaved linear sequences that progress over time, with each linear sequence producing a releasable “increment” of the software.

When using the Incremental model, the first increment is often the core product. Customer usage and evaluation of each increment serve as new features and functions for the next increment’s release. This process repeats after each increment’s release until the final, complete product is created. The Incremental model emphasizes that each increment delivers an operable product.

As a variant of the Waterfall model, the Incremental model possesses all of the Waterfall model’s advantages. Additionally, it offers these benefits: the first deliverable version requires little cost and time; the risk involved in developing small systems represented by increments is low; user requirement changes can be reduced due to the quick release of the first version; and incremental investment is possible, meaning that at the start of a project, one might only invest in one or two increments.

The Incremental model has the following drawbacks: if user change requests are not planned for, initial increments might cause instability in later ones; if requirements are not as stable and complete as initially thought, some increments might need re-development and re-release; and the complexity of managing costs, schedules, and configurations might exceed the organization’s capabilities.

Evolutionary Models

Software, like other complex systems, evolves over time. During development, teams often face scenarios where business and product requirements frequently change, making the final product difficult to realize; strict delivery timelines prevent development teams from fully completing a software product, yet a limited-functionality version must be delivered to meet competition or business pressure; or core product and system requirements are well understood, but detailed issues for product or system expansion remain undefined. In these and similar situations, software developers need a process model specifically designed to handle evolving software products.

Evolutionary models are iterative process models that enable software developers to gradually develop more complete software versions. They are particularly suitable when there’s a lack of accurate understanding of software requirements. Typical evolutionary models include the Prototype model and the Spiral model.

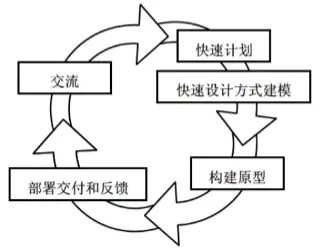

Prototype Model

Not all requirements can be defined upfront. Extensive practice shows that it’s often hard to get a complete, accurate requirements specification early in development. This is mainly because clients often can’t precisely articulate all their future system needs, and developers may have a vague understanding of the application problem to be solved, leading to specifications that are frequently incomplete, inaccurate, or even ambiguous. Furthermore, users might generate new requirements throughout the development process, causing changes. Since the Waterfall model struggles with such requirement uncertainty and flux, a new development method called Rapid Prototype emerged. The prototyping approach is well-suited for situations with unclear or frequently changing user requirements. It’s often a good choice when the system size is not too large or overly complex.

A prototype is an executable version of the intended system, reflecting a selected subset of its properties. A prototype doesn’t need to meet all constraints of the target software; its goal is quick, low-cost construction. Of course, the ability to use prototyping comes from the rapid advancement of development tools, allowing for the quick creation of a tangible system framework for users. This way, users less familiar with computers can propose their requirements based on this framework. Developing a prototype system first involves defining user requirements, developing an initial prototype, then soliciting user feedback for improvements on the initial prototype, and modifying the prototype based on that feedback.

The Prototype model starts with communication, aiming to define overall software goals and identify requirements. Then, a plan for prototype development is quickly formulated, defining the prototype’s objectives and scope. It’s modeled using rapid design and then constructed. The developed prototype should be delivered to the client for use, and client feedback is collected. This feedback can then be used to refine the prototype in the next iteration. When the previous prototype needs improvement or its scope needs to be expanded, the next round of iterative prototype development begins.

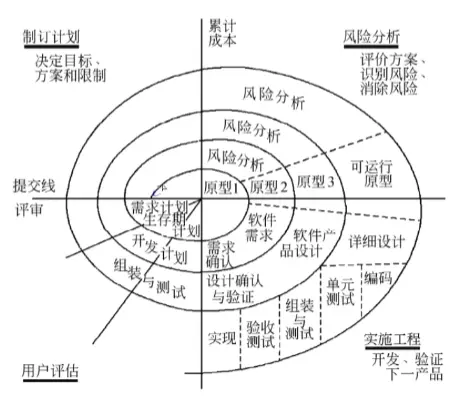

Spiral Model

For complex, large-scale software, developing a single prototype often falls short. The Spiral model combines the Waterfall and Evolutionary models, incorporating risk analysis, which both earlier models largely overlooked, thus compensating for their shortcomings.

The Spiral model divides the development process into several ‘spiral cycles,’ each roughly aligning with the Waterfall model. Each spiral cycle consists of the following 4 steps:

- Planning. Define software objectives, select implementation alternatives, and clarify project development constraints.

- Risk Analysis. Analyze selected alternatives, identify risks, and eliminate them.

- Engineering. Implement software development and verify phase-specific products.

- Customer Evaluation. Evaluate development work, propose corrections, and establish the development plan for the next cycle.

The Spiral model emphasizes risk analysis, enabling developers and users to understand the risks emerging at each evolutionary layer and respond accordingly. Thus, this model is particularly suited for large, complex, and high-risk systems.

Compared to the Waterfall model, the Spiral model supports dynamic changes in user requirements, facilitates user involvement in all key software development decisions, helps improve software adaptability, and provides convenience for project managers to adjust management decisions in a timely manner, thereby reducing software development risks. When using the Spiral model for software development, developers need considerable experience and expertise in risk assessment. Additionally, too many iterations can increase development costs and delay submission times.

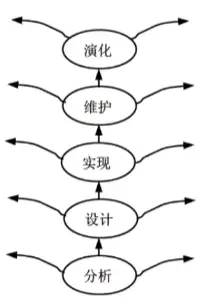

Fountain Model

The Fountain model is a user-requirement-driven and object-driven model, suitable for object-oriented development methods. It overcomes the Waterfall model’s limitations in not supporting software reuse and integration of multiple development activities. The Fountain model makes the development process iterative and seamless.

Iteration means that development activities in the model often need to be repeated multiple times, continuously refining the software system during the iterative process. ‘Seamless’ refers to the absence of clear boundaries between development activities (like analysis, design, coding). That is, unlike the Waterfall model where design begins only after requirements analysis, and coding only after design, the Fountain model allows development activities to overlap and iterate.

The Fountain model’s stages have no distinct boundaries, allowing developers to work concurrently. Its advantage is improved software project development efficiency and reduced development time. However, because the Fountain model’s development stages overlap, it requires a large number of developers during the process, which can complicate project management. Additionally, this model demands strict document management, increasing auditing difficulty.

Unified Process (UP) Model

The Unified Process model is a “use-case and risk-driven, architecture-centric, iterative, and incremental” development process, supported by UML methods and tools. Iteration means dividing the entire software development project into many small “mini-projects,” each containing all elements of a normal software project: planning, analysis and design, construction, integration and testing, and internal and external release.

The Unified Process defines 4 technical phases and their artifacts:

Inception Phase

The Inception phase focuses on project startup activities. Key work products include the Vision Document, initial use-case model, initial project glossary, initial business use cases, initial risk assessment, project plan (phases and iterations), business model, and one or more prototypes (if needed).

Elaboration Phase

The Elaboration phase conducts requirements analysis and architectural evolution after understanding the initial domain scope. Key work products include the use-case model, supplementary requirements, analysis model, software architecture description, etc.

Construction Phase

The Construction phase focuses on system building, producing the implementation model. Key work products include the design model, software components, integrated software increments, test plans and procedures, test cases, and supporting documentation.

Transition Phase

The Transition phase focuses on software delivery work, producing software increments. Key work products include the delivered software increment, beta test reports, and integrated user feedback.

Each iteration produces a baseline including a partially complete version of the final system and any associated project documentation. Baselines are gradually built upon each other through successive iterations until the final system is complete. Each iteration has 5 core workflows:

- Requirements workflow to capture what the system should do.

- Analysis workflow to elaborate and structure requirements.

- Design workflow to realize requirements within the system architecture.

- Implementation workflow to construct the software.

- Test workflow to verify if the implementation works as expected.

As UP phases progress, the effort for each core workflow changes. The 4 technical phases are terminated by major milestones:

- Inception Phase: Lifecycle Objective

- Elaboration Phase: Lifecycle Architecture

- Construction Phase: Initial Operational Capability

- Transition Phase: Product Release

A typical representative of the Unified Process is RUP (Rational Unified Process). RUP is a commercial extension of UP, fully compatible with UP, but more complete and detailed.

Agile Methods

The overall goal of Agile development is to satisfy customers through “early and continuous delivery of valuable software.” By introducing flexibility into the software development process, Agile methods allow users to add or change requirements later in the development cycle.

There are many typical Agile process methods, each based on a set of principles that embody the philosophy proclaimed by Agile methods (the Agile Manifesto).

1. Extreme Programming (XP)

XP is a lightweight (agile), efficient, low-cost, flexible, predictable, and scientific software development approach. It consists of 4 interrelated parts—values, principles, practices, and activities—which are interconnected and permeate the entire lifecycle through activities.

- 4 Core Values: Communication, Simplicity, Feedback, and Courage.

- 5 Core Principles: Rapid Feedback, Assumed Simplicity, Incremental Change, Embracing Change, and Quality Work.

- 12 Key Practices:

- The Planning Game (quickly formulate plans, refine as details evolve).

- Small Releases (design systems for the earliest possible delivery).

- Metaphor (find appropriate metaphors to convey information).

- Simple Design (address only current requirements, keep designs simple).

- Test-Driven Development (write tests first, then write the code).

- Refactoring (re-examine requirements and designs, explicitly re-describe them to align with new and existing needs).

- Pair Programming.

- Collective Code Ownership.

- Continuous Integration (provide runnable versions to customers daily, even hourly).

- 40-Hour Week (work 40 hours per week).

- On-Site Customer (an end-user representative should collaborate full-time with the XP team).

- Coding Standards.

2. Crystal Methods

Crystal Methods posit that every different project requires a unique set of strategies, conventions, and methodologies.

It believes people significantly impact software quality, so as project quality and developer skills improve, so do project and process quality. Improved communication and frequent deliveries boost software productivity.

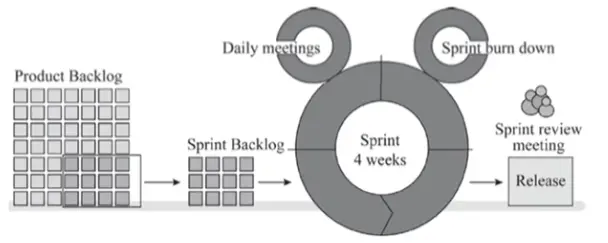

3. Scrum

Scrum uses an iterative approach, where each 30-day iteration is called a “sprint,” and products are implemented according to requirement priorities. Multiple self-organizing and autonomous teams incrementally implement the product in parallel. Coordination happens through brief daily stand-up meetings, much like a rugby “scrum.” The steps are as follows:

4. Adaptive Software Development (ASD)

ASD has 6 core principles:

- Guided by a mission.

- Features are viewed as key points of customer value.

- Waiting in the process is important; thus, “rework” is as crucial as “doing.”

- Change is not seen as correction but as an adjustment to the realities of software development.

- Fixed delivery times compel developers to carefully consider key requirements for each produced version.

- Risk is inherent.

5. Agile Unified Process (AUP)

The Agile Unified Process (AUP) uses the principles of “continuous on the large scale” and “iterative on the small scale” to build software systems. It adopts the classic UP phased activities (Inception, Elaboration, Construction, and Transition), providing a series of activities that enable teams to conceptualize a comprehensive process flow for software projects. Within each activity, a team iteratively uses Agile practices and delivers meaningful software increments to end-users as quickly as possible. Each AUP iteration performs the following activities:

- Modeling. Create model representations of the business and problem domain, models that are “good enough” for the team to move forward.

- Implementation. Translate models into source code.

- Testing. Like XP, the team designs and executes a series of tests to find errors and ensure the source code meets requirements.

- Deployment. Deliver software increments and obtain end-user feedback.

- Configuration and Project Management. Focus on change management, risk management, and control over any of the team’s artifacts. Project management tracks and controls the development team’s progress and coordinates team activities.

- Environment Management. Coordinate process infrastructure such as standards, tools, and supporting technologies applicable to the development team.