Object-Oriented (OO) is a highly practical, systematic approach to software development.

Procedural vs. Object-Oriented

Let’s kick things off with a classic problem: How many steps does it take to put an elephant in a refrigerator?

Typically, you open the fridge, put the elephant in, then close the fridge.

Procedural Approach

Here, you focus on how to do something, implementing the feature step-by-step.

For the elephant problem:

- I open the refrigerator.

- I put the elephant inside.

- I close the refrigerator door.

Object-Oriented Approach

This approach focuses on who should do what. You call operations on objects to achieve functionality.

For the elephant problem:

Create objects: Elephant, Refrigerator.

- Refrigerator opens door.

- Elephant gets into refrigerator.

- Refrigerator closes door.

Object-Oriented Fundamentals

Object-Oriented = Objects + Classification + Inheritance + Communication via Messages.

If your software system uses these four concepts, it’s object-oriented.

Objects

The real world consists of many concrete things, events, concepts, and rules. All of these can be viewed as objects.

In OO systems, an object is the fundamental runtime entity. It encapsulates both data (attributes) and operations (behaviors) that act on that data. An object typically has three parts: an object name, attributes, and methods.

Messages

A message is a construct for communication between objects. When a message is sent to an object, it contains information asking the receiving object to perform certain activities. The receiving object interprets the message and then responds.

Think of it like passing arguments in a method call.

Classes

A class defines a group of generally similar objects. The methods and data within a class describe the common behaviors and attributes of a group of objects. Abstracting and storing common characteristics of objects in a class is a key aspect of OO technology. Whether a rich class library has been built is a significant indicator of an object-oriented programming language’s maturity.

A class is an abstraction above objects, and an object is a concrete realization or instance of a class. During analysis and design, we usually focus on classes rather than specific objects. You don’t define each object individually; instead, you define the class, and then assign different values to its attributes to get object instances of that class.

Classes can be categorized into three types: entity classes, interface classes (boundary classes), and control classes. Control class objects manage activity flows, acting as coordinators.

Some classes have a general-special relationship: some classes are special cases of another class, and one class is a general case for others. A special class is a subclass of a general class, and a general class is a superclass of a special class.

Often, a class and all its objects are referred to as “classes and objects” or “object classes.”

Method Overloading

Method overloading forms:

- Same method name, different number of parameters.

- Same method name, different parameter types.

- Same method name, different parameter type order.

Taking Java as an example, the format for a Java function (method) is as follows:

| |

Here’s an example:

| |

The Three Pillars of Object-Oriented Programming

The three fundamental characteristics of object-oriented programming are: Encapsulation, Inheritance, and Polymorphism.

Encapsulation

Encapsulation is an information-hiding technique. Its goal is to separate the user of an object from its producer, and to decouple an object’s definition from its implementation. From a programmer’s perspective, an object is a program module; from a user’s perspective, an object provides the desired behavior.

Essentially, it’s about packaging real-world entities into abstract classes. A class can then allow only trusted classes or objects to operate on its data and methods, hiding information from untrusted ones.

| |

Inheritance

Inheritance is the mechanism by which parent and child classes share data and methods. It’s a relationship between classes where, when defining and implementing a class, you can build upon an existing parent class, using its defined content as your own, and adding new content.

A parent class can have multiple child classes, all of which are special cases of the parent. The parent class describes their common attributes and methods. A child class can inherit attributes and methods from its parent (or ancestor) class; these don’t need to be defined in the child class, which can also define its own attributes and methods.

If a child class inherits from only one parent, it’s called “single inheritance.” If a child class has two or more parent classes, it’s called “multiple inheritance.”

Note: In Java, a child class can only have one parent class.

| |

Polymorphism

When an object receives a message, it responds. Different objects receiving the same message can produce entirely different results; this phenomenon is called polymorphism. With polymorphism, users can send a general message, and the specific implementation details are determined by the receiving object. This way, the same message can invoke different methods.

Polymorphism is supported by inheritance. By leveraging the hierarchical relationships of classes, messages with common functionality are placed at higher levels, while the different behaviors that implement this functionality are placed at lower levels. Objects created at these lower levels can then respond differently to the common message.

| |

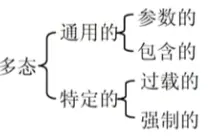

Forms of Polymorphism

Polymorphism comes in different forms. Cardelli and Wegner categorized it into four types:

Parametric Polymorphism: Widely applied, often called the purest form of polymorphism.

Inclusion Polymorphism: Found in many languages, the most common example is subtyping, where one type is a subtype of another.

Overload Polymorphism: The same name represents different meanings in different contexts.

Dynamic vs. Static Binding

Binding is the process of linking a procedure call to the code executed in response to that call. In typical programming languages, binding occurs at compile time, known as static binding. Dynamic binding, however, happens at runtime. Thus, a given procedure call isn’t linked to its code until the call actually occurs.

Dynamic binding is tied to class inheritance and polymorphism. In an inheritance hierarchy, a child class is a special case of its parent, meaning a child object can appear wherever a parent object is expected. Therefore, during runtime, when an object sends a message requesting a service, the requested operation is linked to the implementing method based on the specific type of the receiving object – this is dynamic linking.

Object-Oriented Analysis

The goal of Object-Oriented Analysis (OOA) is to gain an understanding of the application problem. This understanding aims to define the system’s functional and performance requirements.

Object-Oriented Analysis involves 5 activities: identifying objects, organizing objects, describing object interactions, defining object operations, and defining internal object information.

Object-Oriented Design

Object-Oriented Design (OOD) transforms the analysis model created during OOA into a design model, aiming to define the system’s construction blueprint. Typically, when an analysis model generated from a conceptual model is deployed into its corresponding execution environment, implementation issues need consideration, leading to adjustments and additions (e.g., modifying class structure based on whether the programming language supports multiple inheritance or inheritance in general). There’s no chasm between OOA and OOD; they use consistent concepts and notations. OOD also adheres to design principles like abstraction, information hiding, functional independence, and modularity.

Object-Oriented Design Activities

Building upon the OOA model, OOD includes the following five corresponding activities:

- Identify Classes and Objects

- Define Attributes

- Define Services

- Identify Relationships

- Identify Packages

Object-Oriented Design Principles

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) A class should have only one reason to change. That is, when a class needs modification, there should be only one specific reason for it. A class should handle only one type of responsibility.

Open/Closed Principle (OCP) Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) Subtypes must be substitutable for their base (parent) types. This means that anywhere a parent class appears, an instance of its child class can be assigned to the parent type’s reference. An ‘is-a’ relationship truly exists only when an instance of a subtype can replace any instance of its supertype.

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) Abstractions should not depend on details; details should depend on abstractions. That is, high-level modules should not depend on low-level modules; both should depend on abstractions.

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) Clients should not be forced to depend on methods they do not use. Interfaces belong to clients, not to the class hierarchy they’re part of. Essentially: depend on abstractions, not concretions. Also, at the abstraction level, there should be no dependence on details. The benefit of this is maximizing adaptability to potential changes.

These are the five main principles in object-oriented methodology. In addition to these five, Robert C. Martin proposed several other object-oriented design principles:

Release Reuse Equivalency Principle (REP) The granule of reuse is the granule of release.

Common Closure Principle (CCP) All classes in a package should be closed together against the same kinds of changes. If a change affects a package, it should affect all classes within that package, but no other packages.

Common Reuse Principle (CRP) All classes in a package should be reused together. If you reuse one class from a package, you should reuse all classes from that package.

Acyclic Dependencies Principle (ADP) The package dependency graph must not contain cycles. That is, the structure between packages must be a directed acyclic graph.

Stable Dependencies Principle (SDP) Depend in the direction of stability.

Stable Abstractions Principle (SAP) The abstractness of a package should be proportional to its stability.

Object-Oriented Testing

As for testing, systems developed with an object-oriented approach are tested no differently from systems developed with other methods.

Generally, testing for object-oriented software can be conducted at the following four levels:

- Algorithm Layer

- Class Layer

- Template Layer

- System Layer

Object-Oriented Programming

A Programming Paradigm is the fundamental style or model people adopt when designing programs. It dictates the mindset and tools used during programming and has a specific scope of application. Its evolution has moved from procedural programming, modular programming, functional programming, and logic programming, to the current object-oriented programming paradigm.

The essence of Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is using an Object-Oriented Programming Language (OOPL) and applying objects, classes, and related concepts in programming. Its key lies in the addition of classes and inheritance, which further enhances the level of abstraction. Specific OOP concepts are generally manifested through particular language mechanisms within an OOPL.

OOP has now expanded into the realm of system analysis and software design, leading to the concepts of Object-Oriented Analysis and Object-Oriented Design, which we’ve touched upon earlier.