These notes were likely written around the same time as previous ones. Since the file creation time is past the exam date, it might have been created during a file move.

The Role of Operating Systems

A computer system consists of two parts: hardware and software. A computer without any software is often called “bare metal.” Using bare metal directly is not only inconvenient but also significantly reduces work efficiency and machine utilization. The Operating System (OS) aims to bridge the gap between humans and machines, creating an interface between the user and the computer. It’s a type of system software configured for bare metal.

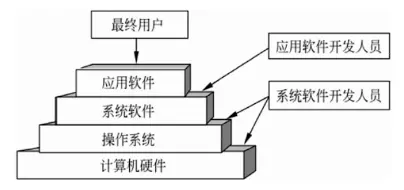

The OS’s position in a computer system is illustrated below:

As shown in the diagram, the OS is the first layer of software on bare metal, extending the hardware’s functionality for the first time. It holds a crucial and special position in a computer system. All other software, such as editors, assemblers, compilers, database management systems, and a wide array of application software, are built upon the OS, relying on its support and services.

From a user’s perspective, once a computer has an OS, users no longer directly interact with the hardware. Instead, they use the commands and services provided by the OS to operate the computer. The OS has become an indispensable and the most important system software in modern computer systems, thus serving as the interface between the user and the computer.

Process Management

Process management is also known as processor management. In multi-program batch processing systems and time-sharing systems, multiple programs execute concurrently. To describe the dynamic changes during program execution in such systems, the concept of a process was introduced. A process is the basic unit for resource allocation and independent execution. Process management primarily focuses on studying the concurrent characteristics of various processes, as well as issues arising from inter-process cooperation and resource contention.

Characteristics of Sequential Program Execution

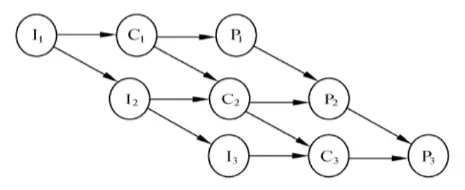

A precedence graph is a directed acyclic graph composed of nodes and directed edges. Nodes represent operations of different program segments, while directed edges between nodes indicate a precedence relationship. The precedence relationship between program segments Pi and Pj is denoted as Pi→Pj, where Pi is the predecessor of Pj, and Pj is the successor of Pi. This means Pj can only execute after Pi has finished.

The image below shows a precedence graph with 3 nodes. Input is a predecessor to calculation; calculation can only proceed after input is complete. Calculation is a predecessor to output; output can only proceed after calculation is complete.

Key characteristics of sequential program execution include sequentiality, closedness, and reproducibility.

Characteristics of Concurrent Program Execution

If multi-programming techniques are used in a computer system, multiple programs in main memory can be in a concurrent execution state. For the job type with 3 program segments mentioned above, although program segments with precedence relationships within the same job cannot execute in parallel on the CPU and I/O components, program segments within the same job that lack precedence relationships, or program segments from different jobs, can execute in parallel on the CPU and various I/O components. For instance, in a system with one CPU, one input device, and one output device, the precedence graph is as follows:

The characteristics of concurrent program execution are:

- Loss of program closedness.

- No longer a one-to-one correspondence between program and machine execution activities.

- Mutual constraints between concurrent programs.

Process States and Transitions

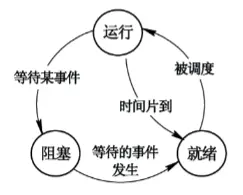

In a multi-program system, processes run alternately on the processor, and their states continuously change. Thus, processes generally have 3 basic states: running, ready, and blocked.

- Running. When a program is executing on the processor, the process is said to be in a running state. Obviously, for a single-processor system, there is only one process in the running state.

- Ready. A process that has acquired all necessary resources except the processor, and can run as soon as it gets the processor, is said to be in a ready state.

- Blocked. Also called the waiting or sleeping state. A process temporarily stops execution while waiting for a specific event to occur (e.g., waiting for I/O completion after an I/O request). In this state, even if the processor is allocated to the process, it cannot run. Hence, it’s called a blocked state.

| Process State | CPU | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Running | √ | √ |

| Ready | × | √ |

| Blocked | × | × |

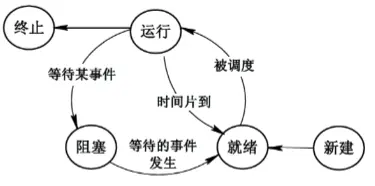

Five-State Model

In reality, for an actual system, process states and their transitions are more complex. For example, introducing “New” and “Terminated” states forms the five-state process model.

Inter-Process Communication

In a multi-program environment, with multiple processes that can execute concurrently, issues of resource sharing and mutual cooperation between processes inevitably arise. Inter-process communication (IPC) refers to the process by which various processes exchange information.

Synchronization vs. Mutual Exclusion: Synchronization deals with direct constraints between cooperating processes, while mutual exclusion deals with indirect constraints between processes contending for critical resources.

Process Synchronization

In a computer system, multiple processes can execute concurrently, each advancing at its own independent, unpredictable speed. However, they need to coordinate their work at certain specific points when cooperating. For instance, if Process A is putting data into a buffer, Process B must wait until Process A’s operation is complete.

Thus, process synchronization refers to the coordination required among processes that need to cooperate and work together within the system.

Process Mutual Exclusion

Process mutual exclusion refers to multiple processes in the system executing exclusively due to contention for a critical resource. In a multi-program environment, processes can share various resources. However, some resources can only be used by one process at a time. These are called Critical Resources (CR), such as printers, shared variables, and tables.

Principles of Critical Section Management

A Critical Section (CS) is the part of a process’s code that operates on a critical resource. The four principles for managing mutually exclusive critical sections are:

- Enter if Empty. If no process is currently in the critical section, a process is allowed to enter it, and it should run for only a finite time within the critical section.

- Exclusive Access. If a process is in the critical section, other processes attempting to enter must wait, ensuring mutually exclusive access to the critical resource.

- Bounded Waiting. For processes requesting access to a critical resource, it should be guaranteed that the process can enter the critical section within a finite amount of time, preventing “starvation.”

- Yield Processor if Waiting. When a process cannot enter its critical section, it should immediately release the processor (CPU) to avoid busy-waiting.

Semaphore Mechanism

The semaphore mechanism, proposed by Dutch scholar Dijkstra in 1965, is an effective tool for process synchronization and mutual exclusion. Currently, semaphore mechanisms have evolved significantly, mainly including integer semaphores, record semaphores, and semaphore set mechanisms.

Integer Semaphores and PV Operations

A semaphore is an integer variable, assigned different values based on the controlled object. Semaphores are divided into two categories:

- General Semaphores. Used to achieve mutual exclusion between processes, initially valued at 1 or the number of available resources.

- Private Semaphores. Used to achieve synchronization between processes, initially valued at 0 or some positive integer.

The physical meaning of semaphore S: S ≥ 0 indicates the number of available resources. If S < 0, its absolute value represents the number of processes waiting for that resource in the blocked queue.

For every process in the system, its correct operation depends not only on its own correctness but also on its ability to correctly implement synchronization and mutual exclusion with other related processes during execution. PV operations are common methods for implementing process synchronization and mutual exclusion. P and V operations are low-level communication primitives and are indivisible during execution. The P operation requests a resource, and the V operation releases a resource.

Definition of P Operation

S := S - 1. If S ≥ 0, the process executing the P operation continues. Otherwise, the process is set to a blocked state (due to no available resources) and inserted into the blocked queue.

The P operation can be represented by the following procedure, where Semaphore indicates that the defined variable is a semaphore:

| |

Definition of V Operation

S := S + 1. If S > 0, the process executing the V operation continues. Otherwise, a process is awakened from the blocked state and inserted into the ready queue, then the process executing the V operation continues.

The V operation can be represented by the following procedure:

| |

Implementing Process Mutual Exclusion with PV Operations

For example, the following two processes might lead to incorrect changes in the COUNT value:

| |

Let the initial value of the mutex semaphore be 1. Execute a P operation to lock the resource before entering the critical section, and a V operation after leaving it. The code is as follows:

| |

Recommended viewing: 【操作系统】进程间通信—互斥 (Operating Systems: Inter-Process Communication - Mutual Exclusion)

Implementing Process Synchronization with PV Operations

Process synchronization arises from mutual constraints due to process cooperation. To achieve process synchronization, a semaphore can be linked to a message. When the semaphore’s value is 0, it means the desired message has not been produced. When its value is non-zero, it means the desired message already exists. Suppose semaphore S represents a certain message. A process can test if the message has arrived by calling the P operation, and notify that the message is ready by calling the V operation. The most typical synchronization problem is the single-buffer producer-consumer synchronization problem.

Recommended viewing: 【操作系统】进程间通信—同步 (Operating Systems: Inter-Process Communication - Synchronization)

Deadlock Caused by Improper Allocation of Homogeneous Resources

If a system has m resources shared by n processes, and each process requires k resources, a deadlock might occur if m < nk, meaning the total number of resources is less than the total required by all processes.

For example, if m=5, n=3, k=3, and the system uses a round-robin allocation strategy, the system first allocates one resource to each process in the first round, leaving two resources. In the second round, the system allocates one more resource to two processes. At this point, no resources are available for allocation, causing all processes to be in a waiting state, leading to system deadlock.

In fact, a deadlock will not occur when m ≥ n × (k - 1).

Deadlock Handling

The main strategies for handling deadlocks are four: the Ostrich Algorithm (i.e., the ignore strategy), prevention strategy, avoidance strategy, and detection and recovery.

Deadlock Prevention

Deadlock prevention involves adopting a strategy to restrict concurrent processes’ resource requests, thereby breaking one of the four necessary conditions for deadlock, ensuring the system never meets the deadlock conditions at any time. Two strategies for deadlock prevention are:

- Pre-allocation (Static Allocation). This breaks the “no preemption” condition by allocating all required resources beforehand, ensuring no waiting for resources. The problem with this method is that it reduces resource utilization and process concurrency; sometimes, required resources cannot be known in advance.

- Resource Ordering Allocation. This breaks the “circular wait” condition by classifying resources and arranging them in a specific order, ensuring no circular wait forms. The problem with this method is that it restricts processes’ resource requests and resource ordering incurs system overhead.

Deadlock Avoidance

Deadlock avoidance aims to break one of the four necessary conditions for deadlock, strictly preventing deadlocks from occurring. Deadlock avoidance does not restrict the necessary conditions as strictly. The most famous deadlock avoidance algorithm is Dijkstra’s Banker’s Algorithm. Deadlock avoidance algorithms typically require significant system overhead.

Recommended viewing: 银行家算法 (Banker’s Algorithm)

Threads

Traditional processes have two fundamental attributes: they are an independent unit for owning resources and an independent unit for scheduling and allocation. Threads were introduced because process creation, destruction, and switching incur significant time and space overhead for the system. Therefore, the number of processes in a system should not be too high, and the frequency of process switching should not be too high, which limits the improvement of concurrency.

With the introduction of threads, these two fundamental attributes of traditional processes are separated. A thread acts as the basic unit of scheduling and allocation, while a process serves as the unit for independent resource allocation. Users can create threads to complete tasks, reducing the time and space overhead when programs execute concurrently.

This way, the basic unit for resource ownership doesn’t need to switch frequently, further increasing the concurrency of programs within the system. It’s important to note that a thread is an entity within a process, a basic unit independently allocated and scheduled by the system. Threads typically own minimal resources (like a program counter, a set of registers, and a stack) but can share all resources owned by their parent process with other threads belonging to the same process.