Core Principles of System Design

Abstraction, Modularity, Information Hiding, Module Independence

Modularity

In software architecture, a module is a unit that can be composed, decomposed, and replaced.

Modularity means breaking down software under development into several smaller, simpler parts, i.e., modules. Each module can be independently developed and tested, then assembled into a complete program. This is a “divide and conquer” principle for complex problems. The goal of modularity is to make the program structure clear, easy to read, understand, test, and modify.

Module Independence

Module independence means each module performs a relatively independent, specific sub-function, with simple connections to other modules. There are two standards for measuring module independence: coupling and cohesion.

Coupling

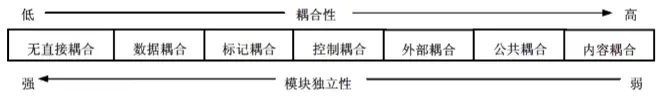

Coupling measures the relative independence (or tightness of connection) between modules. It depends on the complexity of interfaces, how modules are called, and the type of information passed through interfaces. Generally, there are 7 types of coupling between modules:

- No direct coupling. Means two modules have no direct relationship, belonging to different control and call hierarchies, and passing no information between them.

- Data coupling. Two modules have a call relationship, passing simple data values, similar to pass-by-value in high-level languages.

- Stamp coupling. Two modules pass data structures between them.

- Control coupling. One module calls another, passing a control variable. The called module selectively executes a specific function based on the value of this control variable.

- External coupling. Modules are linked via the environment outside the software (e.g., I/O coupling a module to specific devices, formats, communication protocols).

- Common coupling. Coupling between modules interacting through a shared global data environment.

- Content coupling. When one module directly uses another module’s internal data, or jumps into another module’s internal code via a non-standard entry point.

Cohesion

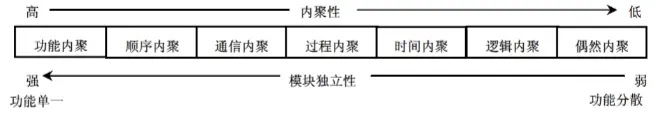

Cohesion measures how tightly bound the elements within a module are to each other. A highly cohesive module (ideally) should do one thing only. Generally, module cohesion is divided into 7 types:

- Coincidental cohesion. Elements within the module have no meaningful relationship.

- Logical cohesion. The module performs several logically similar functions, with a parameter determining which function to execute.

- Temporal cohesion. Actions that need to be performed at the same time are grouped into a module.

- Procedural cohesion. A module performs multiple tasks that must be executed in a specified sequence.

- Communicational cohesion. All elements within the module operate on the same data structure, or use the same input data, or produce the same output data.

- Sequential cohesion. Elements within a module are closely related to the same function and must execute in sequence, where the output of one element becomes the input for the next.

- Functional cohesion. This is the strongest type of cohesion, where all elements within the module work together to achieve a single function, and none can be missing.

Coupling and cohesion are two qualitative standards for module independence. When decomposing a software system into modules, aim for high cohesion and low coupling to enhance module independence.

System Architecture Design Principles

To ensure a successful overall architectural design, these principles should be followed:

- Decomposition-Coordination Principle. The entire system is a whole, with overall goals and functions. However, these goals and functions are realized through the collaborative work of interconnected components. A crucial principle for solving complex problems is to break them down into smaller sub-problems, handling each separately, while coordinating relationships between parts according to overall system requirements.

- Top-Down Principle. First grasp the system’s overall functional objectives, then decompose layer by layer, meaning define the functions of higher-level modules before lower-level modules.

- Information Hiding and Abstraction Principle. Higher-level modules only specify what lower-level modules should do and how they coordinate, but not how they do it. This ensures relative independence and internal structural rationality for each module, leading to clear module hierarchies, and ease of understanding, implementation, and maintenance.

- Consistency Principle. Ensure uniform specifications, standards, and document patterns throughout the entire software design process.

- Clarity Principle. Each module must have clear functions and correct interfaces, eliminating multi-functional and superfluous interfaces.

- Minimize coupling between modules, maximize module cohesion.

- Module fan-in and fan-out should be reasonable. The number of modules directly called by a module is its fan-out; conversely, the number of modules that directly call a given module is its fan-in. Both fan-in and fan-out should be appropriate. Experience shows that a well-designed system typically has an average fan-in/fan-out of 3 or 4, generally not exceeding 7, as higher values can increase error probability. However, menu-driven modules can have larger fan-in/fan-out, and utility modules can have a larger fan-in.

- Appropriate module size. Overly large modules often indicate insufficient system decomposition, potentially containing functions from several parts. Therefore, it’s necessary to further decompose such modules into smaller, as-single-function-as-possible modules. However, decomposition must also be moderate, as excessively small modules can reduce module independence and increase system interface complexity.

- A module’s scope of effect should be within its scope of control.

System Documentation

Information system documentation serves as the “trail” of the system development process, a guide for maintenance personnel, and a communication tool between developers and users. Well-standardized documentation implies that the system was developed using an engineering approach, formally assuring its quality. Missing, informal, or non-standardized documentation can very likely lead to an unmaintainable, unupgradable, unscalable, and lifeless system once the original developers move on.

The various roles of documentation among system developers, project managers, system maintenance personnel, system evaluators, and users are summarized below:

- Users and system analysts communicate through documents during the system planning and analysis phases. These documents primarily include feasibility study reports, overall planning reports, system development contracts, and system design specifications.

- System developers and project managers communicate through documents throughout the project lifecycle. These documents mainly include the system development plan (such as WBS, PERT charts, Gantt charts, and budget allocation tables), monthly development reports, and system development summary reports, among other project management files.

- System testers and system developers communicate through documents. System testers can evaluate the system developed by system developers based on documents like system design specifications, system development contracts, system design documents, and test plans. Testers then compile their evaluation results into a system test report.

- System developers and users communicate during system operation. Users operate the system using documents written by system developers. These documents are primarily user manuals and operation guides.

- System developers and system maintenance personnel communicate through documents. These documents mainly include system design specifications and system development summary reports.

- Users and maintenance personnel communicate during operation and maintenance. While using the information system, users document issues encountered during operation, forming system operation reports and maintenance/modification suggestions. System maintenance personnel then maintain and upgrade the system based on these suggestions and technical manuals left by the system developers.